Seeking a national day

STEPHEN

BROOK

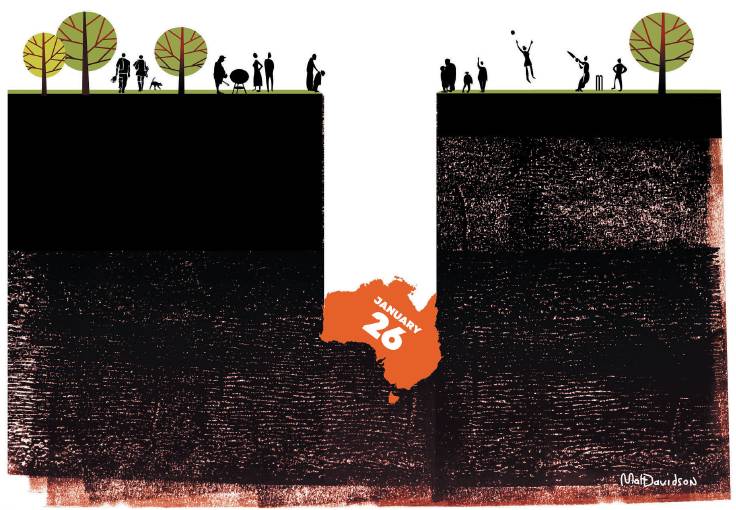

Can we make January 26 a day of celebration and commemoration that encompasses all of us?

As soon as I stepped off the tour bus, the tears appeared. The other Aussies and Brits started to cry. The Turkish tour guide looked teary while the Americans looked solemn but puzzled.

I have never felt more patriotic than during that visit to Anzac Cove. The little beach fringed by the low sandstone wall, the schoolbook history of the failed Anzac campaign suddenly alive and overwhelming, the pride in Australia and Turkey as two enemies that became friends.

I have never felt the same rush on Australia Day, except as a kid during the Bicentenary in 1988, when the final firework exploded across the entire sky, foreshadowing a future full of potential.

Three decades later, have we fulfilled that potential? The Sydney Morning Herald’s coverage of the Bicentenary included professional bon vivant Leo Schofield reporting that ‘‘nothing I’ve seen, not Churchill’s funeral, not Aida at Luxor’’ matched Sydney Harbour’s First Fleet reenactment. But the paper also reported that a lone interjector at the official service at the Customs House served as the Indigenous conscience. A woman carrying a child seized on a pause during Archbishop Clancy’s prayer to cry: ‘‘You tried, but you didn’t get rid of us.’’

Which brings us to Australia Day 2021, as we once again wrestle over annual controversies over Invasion Day and changing the date.

Many think celebrating Australia Day on the day that marked the start of British colonisation is upsetting and offensive to First Nation Australians, as the day represents the beginning of Indigenous dispossession of land and culture.

Where is this debate heading? Like the Flying Dutchman, it sails into view every January and then, with little achieved, glides away forgotten for 11 months. I wrestle with the appropriate way to show genuine lasting respect to First Nations people and the glacial advancement of issues such as the Uluru Statement from the Heart. But I don’t support changing the date. What is the precise change I am agreeing to?

I want Australia Day to be a compelling national celebration and commemoration that encompasses all of us: European settlers, migrants and First Nation peoples.

But I also want to ensure that we accommodate the convict experience in our national day, including that of the youngest First Fleet convict, chimney sweeper John Hudson who was aged nine when he was sentenced to seven years’ transportation for felony. He certainly didn’t sign up for any invasion.

Broadcaster Marc Fennell’s latest ABC podcast, Stuff The British Stole, focuses on how the British pilfered riches from across its Empire, but there was a comment Fennell made at the end of the first episode that really spoke to me. Fennell states that he doesn’t have definitive opinion about British colonialism. ‘‘But as an Australian who’s a bit Indian, a bit Singaporean and a bit Irish, I do know that I wouldn’t exist without it. And depending on where you are listening to this there’s a pretty good chance that you wouldn’t either.’’

I have a similar attitude to Australia Day. When I think about the great progressive campaigns in our history, the 2017 marriage equality campaign and the 1967 referendum to include Aboriginals in the constitution come to mind.

Fifty years later, Samantha Trenoweth paid tribute in the Australian Women’s Weekly to the group of Indigenous suburban women who galvanised political support for change. A key moment came in 1963 when prime minister Robert Menzies invited a delegation from the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement to Parliament House. He offered Kath Walker (who later changed her name to Oodgeroo Noonuccal) a drink. ‘‘If we were in Queensland, you could be jailed for that,’’ she told him. ‘‘The prime minister was shocked and began to reconsider the rights of Aboriginal people,’’ the Weekly wrote.

There is no sign of any of our leaders being shocked into reconsidering Australia Day. It is down to the states and territory governments to change the date. Each state and territory government could create another Australia Day holiday via legislation and pass it into law.

So January 26 remains. Can we make it better? Andrew Parker chairs the Australia Day Council of NSW and believes the day can have different meanings for different people: white, Indigenous and migrant. ‘‘We are unashamedly progressive in what we want Australia Day to be: respectful, reflecting on our past and also celebrate a national day and what it means to be an Australian.’’

I can take that on board and also the thoughts of Chris Lawrence, an Indigenous associate professor at the University of Technology Sydney who heads the Centre for Indigenous Technology Research and Development. Despite having known him for years, I was astonished to find out he was born a noncitizen in 1966 to the Noongar people in Western Australia and automatically placed under the Aboriginal Protection Act, taken to live on the Northam reserve with no running water or sewage. ‘‘This was also part of the White Australia Policy. Apartheid. This was all 55 years ago.’’ Yet he says he ‘‘loves being Australian’’.

‘‘We have brought so many wonderful people there and given them privilege. But for the First Peoples, we still have the most unhealthy, unemployed, uneducated people in this country.’’ For Chris, Australia Day is every day. He will have mixed emotions on Tuesday, which he will celebrate with friends, but also pause to pay respect.

‘‘It is a time to reflect and remember all the people whom we lost.’’

Stephen Brook is a regular columnist.