Restaurant owners step up for migrant workers

HOSPITALITY

Dani Valent

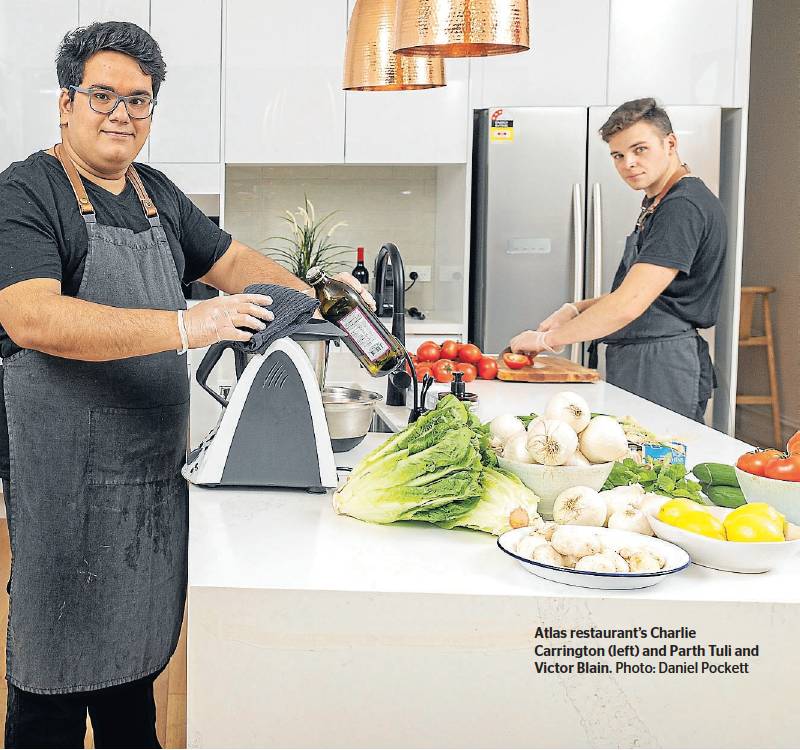

Chef Charlie Carrington has nine employees at his Atlas restaurant in Prahran. Seven of them are from overseas, with visas that allow them to work in Australia but not to claim any benefits.

‘‘I don’t think the government is aware how bad the repercussions are for these workers,’’ Carrington says. ‘‘They are taxpayers, they are here now and we have to look out for them.’’

Despite paying tax, the foreign workers in his restaurant are not eligible for the new JobKeeper payments, nor anything yet announced in terms of a welfare safety net, making them – and his business – particularly vulnerable to the sharp decline in restaurant trade caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. ‘‘Not only would it be bad for them if I couldn’t employ them, it would also be hard for me to start from scratch with new employees on the other side of this,’’ says Carrington.

Coronavirus has forced him to completely rethink his business: on Tuesday, he began delivering ingredient boxes and showing people how to cook dishes using them via online masterclasses. So far, he has been able to keep all his staff busy as they develop the online program.

Among them is Parth Tuli, who has worked at Atlas for two months. The 21-year-old chef came to Melbourne from Delhi to study commercial cookery on a student visa 500, which he’s now transitioned to bridging visa A, a pathway to residency. He is grateful to still be employed when so many he knows are not. ‘‘I’m lucky but all my friends are jobless,’’ he says. ‘‘They are on the verge of being broke and on the street. It will be chaotic.’’

As of December 2019, the Department of Home Affairs reports upwards of 840,000 temporary visa holders with working rights in Australia, most of them students and graduates, with 64,590 classed as temporary residents (skilled) on 482 or 457 visas, and 140,000 working holiday makers. A huge proportion of these legal migrant workers are employed in hospitality and tourism, and they are crucial to the everyday project of feeding Australia. In 2017, migration agents TSS reported that 83 per cent of business owners found it difficult to hire and retain local hospitality workers, which explains the preponderance of foreign workers in those industries.

Already Caterina Borsato, owner of CBD Italian lunch institution Caterina’s, can’t afford to employ her internationals any more. ‘‘I had no choice, I had to put them off,’’ she says. ‘‘But I’ve told them I’ll feed them for free and they can sleep on the restaurant floor if they need to. They are scared and desperate and vulnerable.’’ At Chin Chin, owner Chris Lucas is selling takeaway specifically with his 30 visa holders in mind. ‘‘I’m not making anything from it,’’ he says. ‘‘All the money is going to the visa kids.’’

As well as not being able to claim any assistance, skilled worker visas are often tied to the employer who sponsored them. Unemployment puts visa holders in breach of their residency terms and liable to deportation, but some argue these extraordinary circumstances demand a more nuanced response.

‘‘The government needs to be acting compassionately,’’ says barrister Greg Barns, human rights spokesman for the Australian Lawyers Alliance. ‘‘It would be grossly unfair to seek to deport a person because of a pandemic that causes them to lose their job.’’